SOMERSET

BATH

Hot springs and bathing facilities.

The mythical king

Bladud

is supposed to have been the first to discover the healing springs of

Bath. It

was the Romans, however who have left us the most tangible evidence of

early

occupation. The Roman Baths have been fully excavated at various

periods during the last century and are open to the public, together

with a related museum and recent excavations on the site of the great

temple of Sul Minerva.

| Visitors

can also see the mediaeval King's Bath, the floor of which was removed

in 1980 to allow access to the Roman reservoir beneath, and the Grand

Pump Room where it is still possible to savour a glass of mineral

water, described by Charles Dickens as possessing the ''taste of warm

flat irons'', though most people these days prefer to order tea and

cakes whilst listening to the strains of Couperin played to them by the

Pump Room Trio. About 100 metres to the west, at the far end of the

colonnaded Bath Street lies the Cross Bath, originally a mediaeval (or

possibly even Roman) bath but rebuilt in the late 18th

century to a design by Thomas Baldwin. The bath achieved fame in 1687

when Queen Mary, wife of James II, successfully conceived and delivered

a son after ''taking the waters'' there.

Opposite

the Cross Bath lies the Hot Bath, largely restored to the original

design of John Wood the Younger who built it in 1776 to replace the

mediaeval Hot Bath which lay immediately to the west. A new Spa

building has finally opened after a series of frustrating set-backs. The Hot Bath, which now

connects with the new spa building, and the Cross Bath have both been

redeveloped to provide public mineral water bathing and traditional

spa-style therapy. |

|

| A number of

charitable institutions for the reception of poor visitors and cripples

were established in the city from an early date. Situated close to the baths, the

mediaeval hospital of St John the

Baptist, founded in the 12thC, provides sheltered accommodation for

elderly persons. The current buildings date largely from the 18th and 19th

centuries. |

Ear And Eye Hospital, Walcot Terrace. This tiny

specialist hospital, founded in 1823 is now a funeral parlour. The

front pediment is surmounted by a bust of Hypocrites.

Magdalene Hospital, Holloway.

Once the site of a mediaeval leper hospital, the present building was

used as an ''asylum for idiots'' until the early years of this century.

Hale's Chemist, Argyle Street.

Established in 1826 as a Chemist and Druggist, the business is still a

going concern. The Victorian shop fittings remain largely unchanged and

there is an extensive collection of ''Shop Rounds'' still in situ.

Notice also the fine Coat of Arms on the exterior of the building.

|

Royal National Hospital for Rheumatic Diseases Upper Borough Walls.

|

Founded in 1738, this famous institution was the first national

'specialist' hospitals to be built in this country and opened in 1742

for the reception of impoverished patients whose diseases were amenable

to treatment by the Bath Waters. It remains a specialist hospital but

no longer offers mineral water therapy. The original building was

designed by John Wood and was enlarged, firstly in 1793 by the addition

of an attic storey and later in 1860 by a second building erected on

the west side of the earlier edifice. Little remains of the original

interior, though the basement of the Wood building has suffered the

least alteration.

There is a fine

pediment, in Bath stone, on the 1860 building depicting the parable of

the good Samaritan. The hospital possesses a number of interesting oil

paintings, in particular a picture of Dr Oliver and Mr Peirce

examining three patients in 1741.

|

|

The records of the hospital are incomplete, though there is a complete

set of Minute Books dating from the foundation. A few early admission

registers have been preserved, and there is a book containing c1500

transcriptions of 18th century referral letters often

written by the patients' own doctors and containing much information of

clinical and historical interest. The archival material relating to the

hospital is now kept in the Bath City Archive in the Guildhall.

|

Royal United Hospital. The original

building in Beau Street was, until recently, occupied by city's Technical College. The

present hospital dates from the 1930s and is sited at Combe Park. The earliest

hospital at Combe Park was built to treat injured soldiers returning from the

battlefields of World War I. None of the War Hospital buildings survive. Two

other earlier hospitals on this site remain - the Bath and Wessex Orthopaedic

Hospital (1922) and the Forbes Fraser Hospital (1924) - a small general hospital

for the treatment of those of moderate means who did not wish or could not be

treated at home. It takes its name from a local surgeon.

|

The Eastern Dispensary was established in 1853 and was

one of three such dispensaries in the city where medical and surgical

treatment was available to those of limited means provided they had

obtained a ''Ticket of Recommendation'' from a subscriber to the

charity. The Eastern Dispensary was closed when the NHS was conceived

and the building is currently occupied by a design agency.

|

|

|

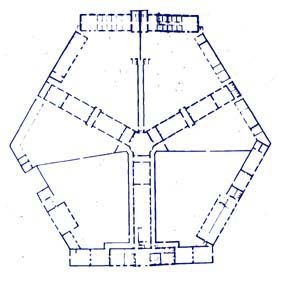

St Martin's Hospital, Frome Road. Built in 1834 as a

work

house using one of Sampson Kempthornes hexagonal plans, it has been

largely redeveloped for residential use. The old psychiatric block is

now used as offices for the local Primary Care Trust. Of interest is a

chapel, purported to have been built single handed by one John Plass,

an alcoholic patient during the early work-house era.

|

Bath had a number of important apothecaries gardens in the 17th and 18th centuries but all trace of these have vanished. However there are several modern medicinal herb gardens here, one at Bath University (in the department of pharmacology) , another at Herschell House, 19 New King Street, and a third at the

American Museum,

Claverton,

a small village about four miles from the city centre. The latter

specialises in herbs from the New World . There is a small shop at the

museum selling traditional American herbal medicines.

Amongst the numerous memorials in Bath Abbey are those to several medical worthies including William Cheselden who died in Bath, supposedly after eating a Bath Bun. His apprentice, Samuel Sharpe is also buried here.

To access a list of medical personnel active in Bath before 1837, click here

CHARD

The town's museum includes a collection of artificial limbs by

Mr James Gillingham, a shoemaker who was a resident of Chard at the end

of the last century.By 1903, Gillingham claimed to have treated over

7000 patients. The business was finally closed in the 1960's.

EDINGTON

Holy well.

Described by Collinson in his History of Somerset as a perpetual spring

containing sulphur and steel. "Against the change of weather, it smells

like the foul barrel of a gun. It is very cold, leaves a white crust on

the bodies it passes over and has been found efficacious in scorbutic

cases." The well still reeks of sulphur though the passing traveller

might mistakenly imagine that the cellophane factory at Bridgwater, not

so many miles up wind of the village, had resumed production. The well

was restored in 1937 in memory of Margaret Charlotte Fownes Lutterell but it is looking rather neglected.

FLAT HOLM (Bristol Channel)

Isolation Hospital, see section on

Wales

GLASTONBURY

Instantly identifiable at a distance from it famous Tor, this small market town was once a popular spa which tried to compete with Bath for patients during the 18th

century. The spring's discovery is attributed to a short-winded local

yeoman, one Matthew Chancelor, who was guided to its position in

October 1750 after a vivid dream. A pump room was constructed over the

source in 1754 and survives as private house in Magdalen Street, next

to the Copper Beech Hotel. The Somerset Rural Life Museum has

a curious example of local folk medicine in the form of a willow tree

with a split trunk through which infants and young children with herniae were

passed in the belief that their ruptures would disappear. ( c.f.

Madron, Cornwall). (The museum also owns a collection of early surgical

instruments but these are not usually on public display and application

to the curator is needed to view.)

KEWSTOKE

|

Woodspring Priory.

Purchased by the Landmark Trust

in

1969, the priory was originally founded in the early thirteenth century

as an Augustinian house. Amongst the surviving buildings which have

been repaired by the Trust is the priory's infirmary.

It measures 44 feet by 20 feet and was originally paved with limestone

slabs of which a few remain. The original entrance was from the

cloisters at the west end but these have long since disappeared. On the

outside south wall, there is a curious semicircular indentation which

marks the position of a former spiral staircase. This was sited in the

infirmary's chapel which was annexed to the south corner of the current

building before its demolition. The staircase probably gave access to

the infirmarer's quarters. There is a notable absence of a fireplace in

the infirmary hall and it has been suggested that heating was provided

by a central hearth, the smoke from which was carried away by a

formerel (a lath and plaster or wicker chimney) which led up to a hole

in the roof, a fine example of fifteenth century arch-brace collar beam

timberwork which has three tiers of windbraces |

|

| After the priory

was dissolved by Henry VIII in 1536, the church suffered an unusual

transformation into a dwelling house, complete with added chimney

stacks built up through the nave. The tower, also dating from the

fifteenth century, was left intact and has been skilfully repaired in

recent years. The infirmary may have been used as a hospital for

wounded soldiers during the 17th and early eighteenth

century as contributions towards such an institution are mentioned in

the local parish records. The last recorded payment was made in 1734.

The infirmary and the church are open to the public during daylight

hours. |

TAUNTON .

St Margaret's Leper

Hospital (left)

in East Reach was founded as a leper hospital in the 12th

century. It was rebuilt in the early 16th century as almshouses, under the

patronage of the Abbot Bere of Glastonbury Abbey.

In 1938 the building was converted to become the headquarters of the Somerset

Guild of Craftsmen and Rural Community Council. In the late 1980s the Guild

moved to other accommodation and the building became derelict, after being

damaged by fire. The Somerset Building Preservation Trust and the Falcon Rural

Housing Association have recently repaired and converted the building into four

small houses.

St Margaret's Leper

Hospital (left)

in East Reach was founded as a leper hospital in the 12th

century. It was rebuilt in the early 16th century as almshouses, under the

patronage of the Abbot Bere of Glastonbury Abbey.

In 1938 the building was converted to become the headquarters of the Somerset

Guild of Craftsmen and Rural Community Council. In the late 1980s the Guild

moved to other accommodation and the building became derelict, after being

damaged by fire. The Somerset Building Preservation Trust and the Falcon Rural

Housing Association have recently repaired and converted the building into four

small houses.

Taunton General

Hospital, South Road. "Standing

on a delightful eminence, at a proper distance from the town in the

midst of a large plot of garden ground...is...a large and very

commodious hospital." But the building with its foundation stone, laid

by Prime Minister Lord North on 29th September 1772 and inscribed "for

the relief of the sick poor" was destined to become a convent. In 1780,

subscriptions to the proposed hospital had fallen so short of their

target that the builders, tired of waiting for their dues, abandoned

the works and left the building to the mercy of vandals and the

elements. As a local historian put it, the incident "blasted the hopes

of the afflicted." The first general hospital at Taunton was ultimately

built in 1812 in East Reach, by which time the original building had

been sold for conversion into a private dwelling for one of the town's

medical practitioners. " The hospital that never was" is now owned by

King's College, one of the town's several Public Schools. It is not

accessible to the public and can only be viewed by special permission

from the school.

SHAPWICK

Holy well. Small

pump room with an enclosed bath was built in 1830 and Dr Beddoes of

Bristol

analyzed the water and proclaimed it on a par with Harrogate water. The

building has long since decayed and is no more than a heap of stones,

though still optimistically referred to as the Bath House.

SWAINSWICK

|

Dr John Haygarth, who moved to Bath from Chester,

is buried in this country parish and there is a memorial plaque on the

wall inside the church. In 1800, Haygarth performed one of the earliest

comparative clinical trials to examine the placebo effect of Perkin's

Tractors, a popular quack cure of the time. |

WELLS

Cathedral

Library. A

former Bishop of Bath and Wells, Nicholas Bubwith, bequeathed money for

building a library over the eastern walk of the cloister in 1424 where

it remains today and houses a

remarkably fine collection of books and incunabula , a considerable

number of which are of medical and scientific interest and include a

five volume set of Aristotle's Works printed in Venice in 1495-8 which

formerly belonged to the famous humanist Erasmus. The library also

possesses works by Avicenna (d.1037) , Ralph Bathurst (1620-1704),

Robert Boyle (1627-1691) and Sir Thomas Browne (1605-1682) as well as

many others. The surviving volumes of the old Bath Abbey library have

been incorporated into this collection and contain a manuscript

believed to have been the work of the prominent 17th century Bath

physician Robert Peirce.

Dr Claver Morris' House. Now

part of Wells Cathedral School, this fine house in the Livery was once

the home of Claver Morris (1659 - 1726) whose diary provides a

fascinating glimpse of the life of a country physician working nearly

three centuries ago. His elaborate

memorial, commemorating fulsomely and in Latin his skills in music,

chemistry and physic, and topped by a bust, can be seen in the

cathedral cloisters. Another house belonging to an 18th medical family

called Pulsford, can be found in New Street (now a bank). The

Pulsfords' Account Book, in the Somerset Record Office at

Taunton, provides an illuminating record of 18th century general

practice. In 1739, quintuplets were born to a woman living in Wells.

The Old Deanery Garden,

9 Cathedral Green commemorates the physician, naturalist and religious

contraversialist, Dr William Turner (1508-1568) who was Dean of Wells

in the 1550s and 1560s. The plants growing in the garden represent a

selection of those mentioned in Turner's Herbal. The garden is open to

the public on Wednesday afternoons during June, July and August.

|

The Mendip Hospital was built in the mid 19th century to the design by Sir Gilbert Scott and served as the County

Asylum. It is an imposing red brick building dominated by a central

spired tower and a chapel in the style of the Gothic Revival. The

buildings, including the chapel (left), have been converted

into dwellings which are now known as St Cuthbert's Village.

|

| WEDMORE |

|

|

Porch House.

The home of Dr John Westover (1643-1706), who

was a pioneer of the humane care of the mentally ill. He succeeded his

father, another John, who practised here until 1678. His

father's tomb in the church is inscribed "Repent, for doctor's dye''

though

much of the gravestone is obscured by the font which was subsequently

placed

over it.

The younger John Westover built the Madhouse alongside

Porch House in 1680 and this still survives. Westover's Journal, an

important manuscript which covers the years 1685-1700, can be viewed in

the Somerset Record Office at

Taunton and downloaded from the web via the Wedmore

Genealogy Pages.

|

|

WIVELISCOMBE

Infirmary.

In 1804, Dr Henry Sully and a surgeon

colleague Mr Bishop Cranmer opened an infirmary and dispensary for the

benefit of "servants, apprentices, labourers and mechanics.'' Dr Sully

was sufficiently well connected to become surgeon to the Duke of

Cumberland who later became King of Hanover. The Wiveliscombe Infirmary

and Dispensary eventually became the premises for the local GPs until

they moved into purpose built premises.

YEOVIL

Penn Villa.

William Hunt first used ether as a dental anaesthetic

in this house at Christmas 1847, a year after its first European use by

London surgeon James Robinson. Hunt's son, also William, published the

earliest English paper on the use of hypodermic injection of cocaine as

a local anaesthetic in 1886. Their house is still a dental surgery more

than a century and a half later.

Gazetteer